The twin sisters untangle their fishing wire in the early morning sun. Their family fled Iraq in early 2016. Lesbos, Greece. April 2017.

Dimitrios and his son on their daily walk along the harbour. Lesbos, Greece. March 2017.

This Spring, I teamed up with journalist Perla Trevizo to investigate what life on Lesbos is like for both refugees and local families. We focused on two families: an Iraqi family who were living in a hotel run by a Greek family, whose grandparents were refugees themselves in 1923.

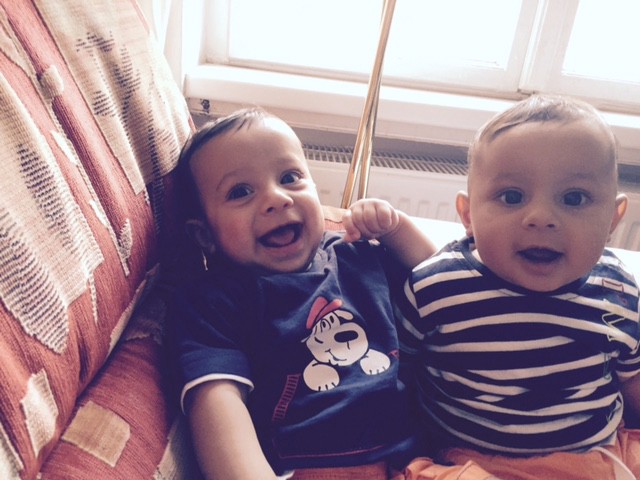

The vivacious ten-year-old twin sisters from Iraq taught us to fish and showed us where they would stash the wire for their early morning fishing expeditions in the harbour near the hotel. They are smart and funny and mischievous. The hotel owner, Dimitrios, along with his mother and sister, shared their family history with us and gave us insight into the current challenges facing locals.

Don't miss the full story, published by Al Jazeera: A crisis within a crisis: Refugees in Lesbos

•

Photos and text by Talitha Brauer, the photographer behind Brother’s Keeper International. Based in Berlin & with regular assignments in Greece, Brauer is active in helping refugees in her local community and seeks to put human faces and stories to complex social issues.